Making the most of your Agility class

Agility classes differ in terms of the experience and expertise of the instructor, focus of the class, conditions and limitations of the site where the classes are held, and other factors outside of the student’s control. To this extent, then, many of the factors influencing the experience of attending an agility class are in other hands than those of the agility student. There are, however, ways in which the student can maximize the benefits that he or she gets from the class by following some simple guidelines.

Come to class with a positive outlook. Expect to do well in class. Don’t look at the sequences or exercises to be performed as impossible tasks. Even if you have trouble with the exercise, don’t let your dog know it. When handlers sigh, complain, or otherwise express their frustration with their own or the dog’s performance, the dog will likely take it as a rebuke and become demotivated. It would be much better to pull out a toy at this point and get rid of your frustration through a game of tug.

When you make a mistake in an exercise (and if you are human you will), stop and reward the dog and then discuss with your instructor what went wrong. Too often students abandon their dogs when something goes wrong, and the dog is left drifting— wondering why mom or dad has suddenly stopped playing.

Be a good citizen and help change jump bars. One of the great challenges of teaching an agility class is making sure that students get the maximum amount of instruction without a lot of “down time.” One way to reduce this amount of down time is to pitch in and help set bars or change the course. The more people who help out, the more time left for running the exercises. Those who run large dogs should be ready to set the bars at an intermediate height while the small dog people are running and while the medium-sized dogs are getting ready to run.

Be ready to do your exercise as soon as the previous dog has finished, unless otherwise instructed by the instructor. If after every dog’s run the next student takes 30 seconds getting ready to go, that’s a lot of lost time.

Another way to save time during class is to confine your dog in a crate, x-pen, or to a post with a leash while you are walking a sequence or otherwise participating in instruction that doesn’t actually require your dog to be active. Frequently, handlers are over-confident in their dogs’ ability to remain in a sit-stay, and they leave their dogs while learning a new sequence. What often happens is that the dog breaks his stay, the handler has to reposition the dog, and valuable time is lost * not to mention the fact that the dog has now learned that maybe the sit-stay is only a suggestion, not a command.

Pay attention to those who run the sequence before you. Not only does watching the other runs reinforce what the sequence or exercise may be, it also gives you some insight into what problems may develop and how you can avoid them. Listen to what the instructor says to correct other students. If you spend the time between your runs as a social hour, you will miss valuable ideas. Save serious socializing for before or after class (arrive early/stay late!) Arrive early, potty your dog, warm your dog up a little should be here somewhere.

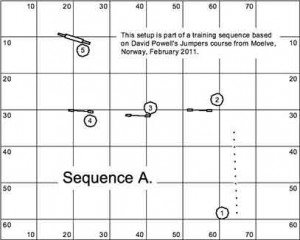

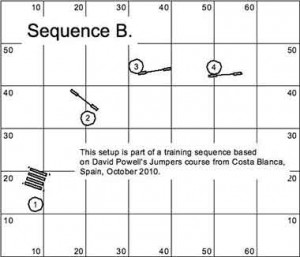

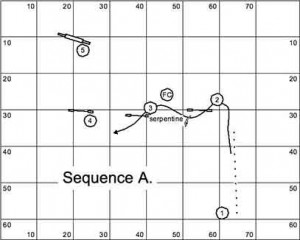

Ask questions and consider bringing a paper and pen to class so you can write down things you learned, things you want to work on, and interesting sequences. Ideally you want to keep a training journal that tracks the progress of your dog. Especially note progress or problems in specific areas: start line stays, tight turns, knocked bars — so that in looking back at your progress over weeks of classes, you can identify what works and what doesn’t.

Provided you aren’t disturbing other members of the class and are able to follow along with what is going on in the session, class time can also be good for working on attention issues with your dog. The distractions may provide you with an opportunity to proof your dog’s ability to remained focused on you.

Whatever other goals you may have for your training, make sure that your dog sees agility training as a positive experience. If you work hard to achieve this goal, your other training goals are thereby more easily attained.